Germany

The study in Germany focused on refugees’ journeys to Europe and people’s transnational networks. More than 70 people were interviewed for the study led by BICC (Bonn International Centre of Conflict Studies).

Special Issue in JEMS

Unsettling Protracted Displacement: Connectivity and Mobility beyond Limbo

Key results and reflections from the TRAFIG project have just been published in a special issue in the Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies (JEMS).

The 9 contributions present novel insights of empirical research in African, Asian and European countries on the role of connectivity and mobility in the lives of displaced people, they critically engage with policies, legal frameworks and structures that keep displaced people in an ongoing state of limbo, they reflect upon the concept of protracted displacement and seek to advance its understanding, and they employ a figurational approach in their analysis.

All 9 articles are freely accessible via the publishers website:

1 Introduction: Unsettling Protracted Displacement: Connectivity and Mobility beyond Limbo

Benjamin Etzold (Bonn International Centre for Conflict Studies, BICC) and Anne-Meike Fechter (University of Sussex)

DOI: 10.1080/1369183X.2022.2090153

Abstract: Conventional understandings of protracted displacement are limited by a number of shortcomings. They imply the stasis of protracted situations; the passivity and disconnection of vulnerable groups who need external support; and immobility of people ‘stuck’ in places. Moreover, solutions to protracted displacement are based on the priorities of states and defined by the perspectives of humanitarian organisations. In contrast, this special issue seeks to advance scholarly and policy debates in order to advocate for more nuanced understandings and genuinely supportive practices of refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs). This is realised through the framework of social figurations of displacement, documenting how these evolve over time, and highlighting the structural forces that perpetuate conditions of displacement. Articles in this special issue demonstrate the agency, resilience and transformative power that lies in displaced persons’ everyday practices. They foreground the role of multiple mobilities in displacement situations, unsettling the politicised concept of protracted displacement as an example of governance techniques that are geared towards locking the lives of forcibly displaced people in space and in time, rendering the displaced populations controllable. Recognising their mobility and connectivity can become a basis to continuously circumventing and challenging these.

2 Is translocality a hidden solution to overcome protracted displacement in the DR Congo?

Carolien Jacobs (Leiden University); Patrick Milabyo Kyamusugulwa; Stanislas Lubala Kubiha; Innocent Assumani; Joachim Ruhamya; Rachel Sifa Katembera (The Social Science Centre for African Development-KUTAFITI)

DOI: 10.1080/1369183X.2022.2090154

Abstract: Policy makers and practitioners usually focus on three durable solutions for IDPs to overcome protracted displacement; return, resettlement and local integration. Based on empirical realities, this paper asks to what extent translocality can be seen as another solution. Drawing on qualitative and quantitative data from the city of Bukavu in eastern DRC, we explore how translocality is shaped in practice and how it helps people to overcome protracted displacement. Translocality of Bukavu’s IDPs is mostly oriented towards the community of origin. We argue that this translocality requires mobility or connectivity, or a combination thereof. Mobilisation of resources in the community of origin can then contribute to the livelihoods of urban IDPs, but restraining forces beyond the control of IDPs can make this a risky and costly strategy that is not necessarily sustainable. Although translocality can address the livelihoods challenges related to protracted displacement, it cannot solve all challenges related to displacement. The paper concludes that translocality should – at most – be seen as a semi-durable and partial solution to move out of protractedness rather than as a durable solution to displacement in itself; however, addressing some of the restraining forces could make it a more durable solution.

3 A matter of time and contacts: Trans-local networks and long-term mobility of Eritrean refugees

Fekadu Adugna (Addis Ababa University); Markus Rudolf (Bonn International Centre for Conflict Studies); Mulu Getachew (Addis Ababa University)

DOI: 10.1080/1369183X.2022.2090155

Abstract: Eritreans have experienced protracted conflict and displacement over the last half a century. Aside from marginalisation, immobilisation, highly constrained livelihood options and legal limbo, this has also created a complex and dynamic web of transnational networks of Eritrean refugees and diasporas around the world. In this paper, we argue that protractedly displaced people are not only entangled with forced immobility but also encounter opportunities to create new migration pathways. This ethnographic study shows how protractedly displaced people build up socio-spatial connections and sequential small-scale mobility, circumventing the multiple constraints the governance regimes have placed upon them.

4 Afghans narrowing mobility options in Pakistan and the right to transnational living

Katja Mielke (Bonn International Centre for Conflict Studies, BICC) and Benjamin Etzold (BICC)

DOI: 10.1080/1369183X.2022.2090156

Abstract: Different types of low-scale mobility have traditionally aided Afghans in Pakistan to cope with the challenges of everyday life during forty years of displacement: cross-border and domestic movement, resource usage from assets ‘back home’, transnational networks, and circular migration conditioned by war, prospects for peace and economic opportunities. However, in the past twenty years, Afghans’ transnational living and mobility have not only become politicised, but mobility options have decreased considerably. This article analyses the underlying immobilisation dynamics, the compression of displacement dimensions, and its effects which translate into Afghans experiencing increasing immobility as forced displacement, accompanied by a feeling of protractedness after spending decades in Pakistan moving freely within the country and cross-border. Based on figurational theory, we argue that the observed linearity of immobilisation dynamics is not inevitable and discuss the potential of Afghans, the governments involved, donors and implementers to change the established figurational dependencies and possibly create alternative solutions that centre on mobility as robust right. Based on our analysis of the socio-political figuration of Afghan refugees in Pakistan – what we call the ARiP figuration – we argue that Afghans should be granted a right to transnational living and mobility.

5 The War Has Divided Us More than Ever: Syrian Refugee Family Networks and Social Capital for Mobility through Protracted Displacement in Jordan

Sarah A Tobin (Chr. Michelsen Institute, CMI); Fawwaz Momani (Yarmouk University); Tamara Al Yakoub (Yarmouk University)

DOI: 10.1080/1369183X.2022.2090157

Abstract: The Syrian crisis began in 2011 in Daràa, near the southern-Syrian border, with the first refugees coming into Jordan thereafter. Over the course of the following years, nearly one million Syrian refugees migrated to Jordan and still reside there, some in the same areas in which they first settled. These settlement patterns are often portrayed in simplistic narratives of Syrian migration that emphasise mobility in a straightforward trajectory. This paper aims to unsettle such narratives by examining the role of Syrian family networks in mobility in Jordan’s northern region, particularly in and between the cities of Mafraq and Irbid, as well as the Zaatari refugee camp. Based on mixed methods, this paper examines the network factors that made Jordan the country of preference and possibility for settlement, the family networks involved in domestic mobility within Jordan, and their influences on aspirations and worries about future movements. Ultimately, the paper finds that pre-crisis economic, social, and familial networks were often employed at key decision-making moments throughout Jordan in mobility trajectories. As time has progressed, however, Syrians in Jordan reported challenges to social capital in the form of mobility assistance from their long-standing family networks.

6 On not staying put where they have put you: Mobilities disrupting the socio-spatial figurations of displacement in Greece

Eva Papatzani (Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and National Technical University of Athens); Panos Hatziprokopiou (Aristotle University of Thessaloniki); Filyra Vlastou-Dimopoulou (Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and National Technical University of Athens); Alexandra Siotou (Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and University of Thessaly)

DOI: 10.1080/1369183X.2022.2090158

Abstract: The reception and protection system in Greece in the aftermath of the so-called refugee crisis produces a geography of specific mobility restrictions and accommodation types for migrants, asylum-seekers and refugees. These restrictions create a multi-layered landscape of displacement, dominated by three socio-spatial figurations: the forced containment of displaced people in ‘hotspots’ on eastern Aegean islands; staying in isolated and segregated camps in the mainland; and the accommodation of the most vulnerable in urban centres. At the same time, the mobility practices of displaced people often disrupt the above figurations, stemming from their survival practices and life aspirations, and largely relating to their translocal social connections. These mobilities include, but are not limited to, unregistered movements from hotspots to the mainland, mobilities from camp to camp, mobility negotiations between camp and city. This paper explores the figurations of displacement related to the impact of governance regimes on the livelihoods and mobility of displaced people in Greece. Within this frame, it focuses on the ways through which migrants and asylum-seekers negotiate, resist or transcend the geography of multiple restrictions, through translocal mobility practices that intervene and therefore reshape dominant socio-spatial figurations.

7 “Exit Italy”? Social and spatial (im)mobilities as conditions of protracted displacement

Pietro Cingolani (Università di Bologna & FIERI); Milena Belloni (Flanders Research Foundation & FIERI); Giuseppe Grimaldi (Università di Trieste & FIERI); Emanuela Roman (FIERI)

DOI: 10.1080/1369183X.2022.2090159

Abstract: This article examines how the experience of protracted displacement interacts with mobility desires and practices of a diverse population of asylum-seekers, refugees and undocumented migrants in Italy. Drawing from ethnographic data collected in different Italian localities and among different nationalities, we focus on participants’ translocal connections, both as ways ‘out of limbo’ and as factors in protracted legal and socio-economic precariousness. We propose an interpretation of complex spatial mobilities to understand under what conditions spatial mobility translates into an improvement in the living conditions of migrants, producing upward socio-economic mobility, and under what conditions spatial mobility perpetuates marginality and isolation. Although translocal connections provide space for action, migrants risk being trapped in a loop of movements between different countries and different localities within Italy, without the possibility to achieve legal protection in any of these.

8 Family figurations in displacement: Entangled mobilities of refugees towards Germany and beyond

Simone Christ (German Institute of Development and Sustainability (IDOS); and Benjamin Etzold (Bonn International Centre for Conflict Studies, BICC)

DOI: 10.1080/1369183X.2022.2090160

Abstract: Refugees rarely flee in isolation. Instead, their everyday lives and mobilities are fundamentally shaped by the broader set of social relations in which they are embedded, particularly by their families. Drawing on interviews with sixty displaced people living in Germany and in-depth case studies of the trajectories of refugees from Eritrea and Syria, we reconstruct the role that families and other social relations transgressing national borders have played in their mobility to Germany and how their lives have been rescaled since initial displacement. Based on central ideas from figurational sociology, which we link with scholarship on forced migration, transnationalism and family relations, our paper identifies four specific family figurations in displacement that represent typical mobility patterns and constellations of ‘doing family’ in transnational spaces: the lone yet connected traveller; the reunited nuclear family; the transnationally separated family; and the transnationally extended family. We argue that family figurations in displacement are, on the one hand, decisively shaped by specific family relations and distinct displacement trajectories with various phases of family separation and reunion. On the other hand, they are fundamentally configured by migration regimes and asylum systems that substantially constrain the opportunities to live dignified local or transnational family lives.

9 The EU and protracted displacement: providing solutions or creating obstacles?

Nuno Ferreira (University of Sussex); Pamela Kea (University of Sussex); Albert Kraler (Danube University Krems); Martin Wagner (International Centre for Migration Policy Development, ICMPD)

DOI: 10.1080/1369183X.2022.2090161

Abstract: In this paper, we explore how the European Union (EU) legal and policy framework relates to protracted displacement. To this end, we examine the existing legal, policy and institutional framework both in the EU and globally, including the Common European Asylum System (CEAS), the 2015 ‘European Agenda on Migration’, and the New Pact on Migration and Asylum. Analytically, we employ Norbert Elias’ concept of ‘figurations’ as a conceptual lens to describe and identify distinct constellations of relationships, norms and social interactions between different actors shaping approaches towards protracted displacement. We argue that policies on protracted displacement are shaped by a triangle of three figurations – the migration-security figuration, the humanitarian-refugee relief figuration, and the protection-rights figuration. We trace how the migration-security figuration has gained the upper hand in recent years and what this means for EU policies addressing protracted displacement. We conclude that the EU is an actor that facilitates, rather than addresses, protracted displacement, and the Pact on Migration and Asylum further cements that role.

TRAFIG practice note no. 11

The missing link

Promoting refugees’ skills-based mobility within Europe

The Common European Asylum System prohibits the mobility of persons entitled to international protection within the European Union, making it more difficult for displaced persons to rebuild their lives even after arriving in Europe and receiving protection status. Recent developments soften this strict policy of immobility for some. In this context, intra-EU mobility based on refugees’ skills could become a game-changer. The tools are there. What is needed now is to connect these initiatives so that more displaced persons can use their skills for their benefit and that of receiving countries. Read more

TRAFIG policy brief no. 7

Creating a way out of the maze: Supporting sustainable futures for displaced persons

As displacement continues to rise globally, more and more people are ‘stuck’ in situations of protracted displacement, where they find themselves in a long-term situation of vulnerability, dependency and legal insecurity, lacking or actively denied opportunities to rebuild their lives. Drawing lessons from more than 3 years of research, this policy brief highlights critical entry points for European stakeholders seeking solutions for (protracted) displacement. Read more

TRAFIG Synthesis report

'Nothing is more permanent than the temporary' – Understanding protracted displacement and people's own responses

Final report sums up findings of 3 1/2 years of TRAFIG research.

Across the world, 16 million refugees and an unknown number of internally displaced persons (IDPs) experience long-lasting conditions of economic precarity, marginalization, rightlessness and future uncertainty. They live under conditions of protracted displacement. Policy solutions often fail to recognise displaced people’s needs and limit rather than widen the range of available solutions.

This report brings together the central findings of the TRAFIG project’s empirical study in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Ethiopia, Tanzania, Jordan, Pakistan, Greece, Italy and Germany. We engaged with more than 3,120 people in our three-year project.

Our analysis centres around five factors that shape conditions of protracted displacement:

- governance regimes of aid and asylum

- social practices and livelihoods

- networks and movements

- intergroup relations between displaced people and hosts

- development incentives and economic interactions

We present multiple findings on each of these themes. Moreover, this report addresses gender and class-based differences and mental health related challenges in constellations of protracted displacement as well as political dynamics that impact on people's own responses to protracted displacement.

Overall, our research shows that refugees, IDPs and other migrants by and large find protection, shelter, livelihood support, a sense of belonging and opportunities to migrate elsewhere through their personal networks. These networks often stretch across several places or even extend across multiple countries. While they are not a panacea for all challenges, people's own connections are an essential resource for sustainable and long-term solutions to their precarious situation. They must not be ignored in policy responses to protracted displacement. Understanding the needs and the local, translocal and transnational ties of displaced people is the foundation for finding solutions that last.

Download our final report here: TRAFIG-synthesis-report-web.pdf

Authors:

Benjamin Etzold, Elvan Isikozlu, Simone Christ, Laura Morosanu, Albert Kraler, Ferruccio Pastore, Carolien Jacobs, Filyra Vlastou, Eva Papatzani, Alexandra Siotou, Panos Hatziprokopiou, Ben Buchenau, Fawwaz Ayoub Momani, Sarah Tobin, Tamara Al Yakoub, Rasheed Al Jarrah

Please cite as:

Etzold, B. et al. (2022). ‘Nothing is more permanent than the temporary’ – Understanding protracted displacement and people's own responses. TRAFIG Synthesis Report. Bonn: BICC. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6490951

TRAFIG @ IMISCOE 2022

Presentations of TRAFIG colleagues at the 19th IMISCOE conference

From 29th June - 1st July, the European network of migration researchers IMISCOE will hold its (hybrid) conference in Oslo (more here).

The conference theme "Migration and Time: Temporalities of Mobility, Governance, and Resistance" fits very well to the interests and foci of our TRAFIG project. 'Protracted displacement' can indeed be understood as a social phenomenon that is shaped by quite specific spatial and temporal politics. While movements of refugees and IDPs can hardly be prevented, governments of (potential) receiving states try to manage displaced populations though particular spatial strategies (border enforcement, encampment, etc.) and through temporal strategies (short-term humanitarian support, mid-term asylum procedures, etc.). As spatial exclusion dominates and long-term solutions are largely absent, displaced people are constantly forced to wait and have to endure extreme future uncertainty. The figurational approach we applied in our TRAFIG research is a concept well suited to analyse the social figurations of displacement in both its spatial and temporal dimensions (more on this in a shortly upcoming special issue in JEMS).

At this years conference, the TRAFIG team will be present with a number of papers that bring to the fore our conceptual approach, empirical data and analysis.

Networked mobility – socially-bound decisions, capacities and barriers to move out of protracted displacement

Sarah Tobin (CMI), Benjamin Etzold (BICC) and Carolien Jacobs (Leiden University) will present a joint paper in a session on "Migration (decision-making) in conflict settings (Part II)" (Session #126) on Thursday June 30, 14:45 - 16:15. [more on the session here]

Abstract:

After initial moves, many displaced persons live under highly precarious conditions and their future perspectives are strongly constrained. Different forms of mobility such as movements out of camps, return mobility, circular mobility or onward moves to other countries are seen by many as the sole way forward in life. But the decision to move again (or not) is rarely taken in isolation. In contrary, research undertaken in the TRAFIG project, which investigated coping strategies to protracted displacement, showed that mobility decisions after displacement are strongly dependent on the social constellations, in which individuals are embedded. These ‘figurations in displacement’ are decisively shaped by (a) governance regimes of aid and protection that assign displaced persons certain socio-legal positions and places of living, and (b) family and kin relations at places of living and across transnational spaces. Our paper presents empirical findings on ‘networked mobility’ and ‘disconnected immobility’ from research across Western Asia (Pakistan, Jordan), East Africa (Ethiopia, DR Congo) as well as Southern (Italy, Greece) and Western Europe (Germany). An analysis of survey (n=1900) results is complemented by in-depth case studies of individuals whose translocal relations and mobilities helped them to ‘move out’ of protractedness, or who remained ‘stuck’ in precarious conditions due to immobilising effects of governance regimes or social disconnections.

Time and temporalities in transnational family figurations under conditions of displacement

Former BICC-colleague Simone Christ, now at the German Institute of Development and Sustainability (IDOS), will give a paper presentation in session 193 on "Temporalities of transnational families" on Friday July 1, 09:00 - 10:30. [more on the session here]

Abstract:

This presentation will focus on the temporalities of transnational family figurations of refugees, bringing together discussions on times and temporalities (Griffiths et al. 2013) with transnational families (Merla et al. 2021, Bryceson & Vuorela 2002, Sauer et al. 2021) and a figurational approach (Elias 1978). Our recent empirical study of family figurations in displacement in the framework of the TRAFIG (Transnational Figurations of Displacement) project showed that displaced people are embedded in different family figurations, which evolve and transform under time. If one parent of a family embarks on an irregular journey alone, the family transforms into the figuration of a “transnationally separated family” in which family members live in different places for an indefinite time. If after arrival in countries such as Germany family reunification is successful, separated families may transform into the “figuration of reunited nuclear families”. If not, the separation can become protracted. Family figurations vary considerably with regards to time. Whereas the transformation into a separated family might appears rapidly, as a family member is forced to flee, the separation due to unsuccessful attempts of family reunification (e.g. for Eritreans) can endure for a long period. Time is decelerated and the outlook into the future insecure; anxious waiting and rising hope alternate with recurring disappointments. Family members experience ambiguous dimensions of time: Whereas on the one hand, time is decelerated, on the other hand, life-cycle time passes too quickly - the lost time of separation between children and their parents cannot be made up for again.

Revisiting the Migration-Development Nexus from a Cross-Border Perspective

Benjamin Etzold will contribute to workshop session #94 taking place on Thursday June 30, 10:45 - 12:15. [more on the session here]

The workshop aims to introduce and expand ways in which our combined expertise in the field of im/mobilities, translocal livelihoods, border communities, migration regimes, displacement dynamics and restructuring of local and regional governance could provide valuable input for addressing the migration-development nexus.

TRAFIG at the “In Dialogue” Symposium organised by Indiana University

On 18/19 March 2022, colleagues involved in the TRAFIG project contribute to Indiana University’s “In Dialogue” Symposium, which focusses on transnational dynamics and repercussions of the movement of displaced peoples between Africa and Europe. In a session on “Constrained transnationalism: Experiences of displacement and ongoing limbo between Africa and Europe” Catherina Wilson (Leiden University), Janemary Ruhundwa (Dignity Kwanza), Benjamin Etzold (BICC), Markus Rudolf (BICC), Simone Christ (formerly BICC) and Pietro Cingolani (FIERI) will share insights from TRAFIG research in Tanzania, Ethiopia, Italy, the Netherlands and Germany.

Meet TRAFIG Team member Simone Christ

Meet Simone Christ, who managed the TRAFIG fieldwork in Germany implemented by the Bonn International Center for Conflict Studies (BICC), and find out more about her experience, her motivation and her work in the TRAFIG project.

Four years ago, we at BICC, in collaboration with our partners, responded to a call by the European Union asking for alternative solutions and innovative ideas for tackling protracted displacement. In our previous research projects on displacement, we saw how people relied on their own resources—particularly connectivity and mobility—to escape protracted displacement despite adverse and constraining conditions. This is where we wanted to start: How can displaced people use mobility and connectivity as resources to get out of the precarious living conditions and the enduring situation of limbo they experience in protracted displacement? Four years later, I can now look at these aspects from the perspective of refugees in Germany, as I led the German case study ... Read more

TRAFIG practice note no. 10

Following their lead

Transnational connectivity and mobility along family figurations in displacement

Transnational lives are not the exception but rather a reality of displaced peoples’ everyday lives. This became obvious in the TRAFIG research with refugees in Germany, which was based on a figurational approach to better understand their situation and how they overcome protracted displacement. By focussing on the social constellations in displacement, a figurational approach can offer practitioners a new way to identify how to best support displaced people.

Everyone belongs to multiple social constellations or ‘figurations’. In the TRAFIG research in Germany, which is presented in TRAFIG working paper no. 10, family figurations of displaced persons were of particular importance, as decisively shape their everyday lives—particularly when refugees have been separated from close family members, and/or when kin networks are dispersed across multiple countries. Read more

TRAFIG policy brief no. 6

Moving on

How easing mobility restrictions within Europe can help forced migrants rebuild their lives

Free movement within the Schengen area is a cornerstone of European integration – and indeed an essential part of the European way of life. However, this freedom of movement is limited for forcibly displaced people residing within the European Union (EU). European asylum systems are designed to suppress mobility, which actually prevents many asylum seekers from finding a ‘durable solution’. In contrast, enabling legal mobility within and across EU countries, when paired with access to labour markets and ensuring the right to family life, can open new opportunities for forced migrants to settle into receiving communities and truly rebuild their lives. Read more

TRAFIG working paper no. 10

Figurations of Displacement in and beyond Germany

Empirical findings and reflections on mobility and translocal connections of refugees living in Germany

This working paper presents the findings of the empirical research on the role of connectivity and mobility for displaced people in Germany in the framework of the TRAFIG project. The findings are based on qualitative fieldwork in Germany, with 73 qualitative interviews with displaced people and experts in the field.

This working paper uses a figurational perspective; figurations are characterised as dynamic social constellations which emerge in the context of displacement between displaced people and state and other actors at the local, translocal and transnational scale. This working paper discusses the figurations of displacement in which refugees in Germany are embedded.

Our analysis demonstrates the importance of family figurations in displacement, among them the “figuration of a transnationally separated family”, “figuration of the jointly displaced family”, or the “figuration of the transnationally extended family”. Family figurations are deeply intertwined with local and transnational bureaucratic figurations, which structure the experiences of refugees. Bureaucratic figurations evolve with respect to German authorities, those of the countries of origin and other local actors. Despite the significance of family figurations, connectivity is not restricted to it. Refugees are also connected within non-kin figurations, such as within an “ethnic network-based” or “volunteer-refugee” figuration.

The analytical category of figurations provides valuable insights into how displaced people embedded in certain social constellations can best be supported. It shows that transnational life is a reality for displaced persons and an integral part of their everyday lives. As the German case demonstrates, displaced people use mobility and connectivity as a way out of protracted displacement.

Authors: Simone Christ, Benjamin Etzold, Gizem Güzelant, Mara Puers, David Steffens, Philipp Themann, Maarit Thiem

Cite as: Christ, S. et al. (2021). Figurations of Displacement in and beyond Germany—Empirical findings and reflections on mobility and translocal connections of refugees living in Germany (TRAFIG working paper no. 10). Bonn: BICC. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.5841892

You can download TRAFIG working paper no. 10 here.

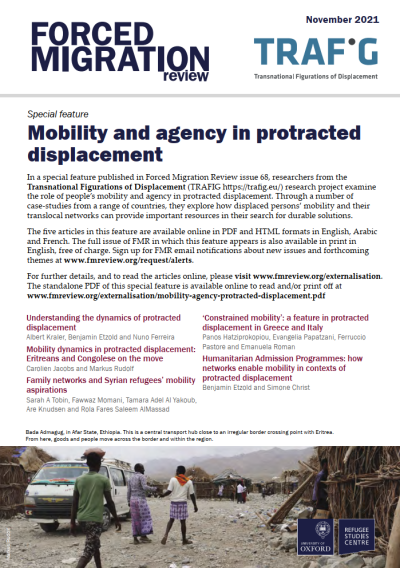

Mobility and agency in protracted displacement

Available in English, French and Arabic

The latest issue of the Forced Migration Review includes a special feature on mobility and agency for those living in protracted displacement, produced in collaboration with the TRAFIG project. Read more

- Understanding the dynamics of protracted displacement

- Mobility dynamics in protracted displacement: Eritreans and Congolese on the move

- Family networks and Syrian refugees’ mobility aspirations

- ‘Constrained mobility’: a feature in protracted displacement in Greece and Italy

- Humanitarian Admission Programmes: how networks enable mobility in contexts of protracted displacement

Forced migration as a fragmented process: (Im)mobility in Una-Sana Canton, Bosnia

Insights from field research at the EU external border in Bosnia and Herzegovina

by Philipp Themann

The Bosnian Canton Una-Sana at the European Union's external border is currently the end of the line for thousands of refugees. With the devastating fire in Camp Lipa just before Christmas, their already precarious situation has become even worse. Even though the humanitarian catastrophe at the border is currently generating a comparatively high interest of the media, no adequate and winterised accommodation for the displaced has yet been found. Despite the warnings of numerous human rights organisations, EU member states have not been able to bring themselves to grant displaced persons safe entry and an examination of their applications for asylum. Some 1,000 people are now living in the former Camp Lipa in winter without shelter, sufficient food, clothing and medical care- not to speak of the many hundreds of people in the ruins and woodlands around the two towns of Bihać and Velika Kladuša. This blog gives an insight into the situation there.

Una-Sana as a space of displacement

Una-Sana Canton is situated in the north-west of Bosnia and Herzegovina, in direct proximity to the Croatian border. The geographical closeness to the EU’s external border and the infrastructural connections make it an ideal starting point for the onward journey of many displaced people to the European Union. This is why the cities of Bihać and Velica Kladuša have been major transit points for refugees on their way to the European Union for several years. Due to the intensified border protection and the illegal push-backs of the Croatian border police, Una-Sana has also become a place where displaced people are forced to stay on. In this way, they are deprived of their chance and right to apply for asylum once they have crossed the border.

In the Canton, forced migrants can be found 1) in central, state-recognised camps, 2) in the periphery of the towns in larger mutually supportive groups in empty houses, industrial buildings, so-called squats or in wooded surroundings of the towns, so-called jungle camps, 3) in various localities in smaller mutually supportive groups in the immediate vicinity to the Croatian border (for instance just before they cross the border) or in some few cases 4) hidden in private houses by Bosnian citizens.

The freedom of movement of these forced migrants is extremely limited as a result of police repression by Bosnian authorities and their being moved to official and informal shelters. Besides police repression, lacking resources to meet (basic) needs and the numerous push-backs by Croatian border officials exacerbate this problem.

Official and informal shelter structure A: Burnt-down Camp Lipa, B: Large squat: Collapsed factory building, C: Smaller squat: Burnt-out house, D: Jungle camp (pictures: Philipp Themann)

Official and informal shelter structure A: Burnt-down Camp Lipa, B: Large squat: Collapsed factory building, C: Smaller squat: Burnt-out house, D: Jungle camp (pictures: Philipp Themann)

(Im)mobility between state-recognised camps, informal squats and the internalised external border of the European Union

In the burned-down Camp Lipa, the precarious living and weather conditions, the remoteness of the camp and lack of alternative housing have led to the fact that residents of the camp have nowhere to go and are increasingly isolated from the rest of the world. This manifests itself, for example, in the fact that some people no longer have the strength to walk longer distances in freezing temperatures and snowfall to change from one place to another or to run away from border police when trying to cross the border.

- “We sleep in a handmade shelter, because there was no other place to live (in the burned-out Camp Lipa). Only half bread and one canned meat and half liter water. For one day. (…) now we do not have energy that we can run. Because of the hunger. The hunger destroyed everything” (Interview 1, male, 30, Afghanistan).

As the holding capacity of the few official camps in Una-Sana is not sufficient to accommodate all, an informal, highly makeshift housing infrastructure has developed in recent years. This includes empty and dilapidated factory halls or uninhabited houses, so-called squats, where refugees organise themselves in separate, autonomous mutually supportive groups. Depending on the size of the building and the season, several hundreds of individuals can live in different rooms and halls of a squat. The inhabitants of such squats are also subject to protracted immobilising forces, determined mainly by the precarious socio-economic living conditions and police repression.

Some refugees report, for instance, that because of arbitrary controls by Bosnian police officers, they cannot move in public spaces or along roads. They are often denied access to public facilities, supermarkets or hospitals. As a result, they generally only leave their informal housing when they intend to cross the border or when they go to get food at night, which is mainly distributed by (criminalised) volunteers. As most squats are in the immediate vicinity of the towns or even in the town centre, their inhabitants are evidently exposed to the permanent danger of being held by Bosnian police officers and deported to Camp Lipa, which is 25 km away even though there is no space for them.

- “They (Bosnian police officers) catch us, sometimes they beat us and then (…) they push us back to Camp Lipa. (…). When IOM (camp authority) recognise that you don’t have ID-Card (proof of living in the camp) they told you ‘leave the Camp, go outside' in the midnight, then we have to walk 4 1/2 hours back in the city” (Interview 2, male, 25, Pakistan).

The combination of police push-backs to the remote camp and being sent away by the camp authority forces refugees to involuntary mobility between official and informal housing infrastructure. Around the towns, they use a network of informal and memorised pathways:

- „We know the way, we go through the forests (due to police controls at public access roadways), there is a little way we cross (beaten paths). (…) Then we come back to main road, if there is no police, and try again to reach here (squat near the city centre)” (Interview 2, male, 25, Pakistan).

Besides the policy of repression in the Una-Sana described above, refugees continue to be hindered in their movement in the Croatian border area. According to the displaced, the problem is not to cross the EU’s external border but to stay on the other side for good. The internalisation of the border seems to extend far into Croatia itself, where refugees are apprehended, deported and forced from the Schengen area back to Bosnia. In this context, many displaced persons report ‘chain push-backs’ with the informal cooperation of Italian, Slovenian and Croatian border officials. The descriptions of the at times violent push-backs are quite drastic in some cases.

- “I tried ten times (to cross the border into the EU). Two times I was deported from Triest (italian city near the Slovenian border) (…) They (border police) catch us in the night, the people were sleeping and don’t recognize that police come. The (Croatian) police beat us everywhere, with sticks, kicks, tear gas and push us back to the Bosnian border. (…) When I see they (Croatian border police) going to beat me, I try to protect my face and body. (…) We don't fight back (…) they might get angrier” (Interview 3, male, 19, Pakistan).

Besides the violent assaults, some Croatian border officials seem to confiscate the personal belongings of the refugees:

- “Croatia police take our sleeping bags, money, mobiles, shoes, jackets, everything they take. I don’t know what they doing with the mobiles and money, but they burn the jackets, bags and shoes in a fire near to the (…) border” (Interview 3, male, 19, Pakistan).

These violent push backs by Croatian border officials and the taking away of personal items contribute greatly to the protracted immobilisation of forced migrants in Una-Sana. Under the precarious socio-economic conditions, it usually takes them some weeks or months to equip themselves for a new attempt at crossing the border. For instance, many reported that they have been stuck in Una-Sana for one to two years and were trying to cross and then to stay on the other side of the border every two months on average, weather permitting.

The findings from this field research indicate that the immobilisation of refugees and their precarious socio-economic living conditions in predominantly informal housing infrastructures is mainly caused by the EU border regime and respective state-organised orders of violence.

The field research took place in the framework of a cooperation with BICC and the TRAFIG project and the data collection for my Master’s thesis at the University of Bonn’s Geography Department between 29 December 2020 and 9 January 2021.The research was made possible by the German association "Kölner Spendenkonvoi e.V.".

The views and opinions expressed in this blog do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the TRAFIG Consortium or the European Commission (EC). TRAFIG is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.

Insights from TRAFIG field work in Germany

By Simone Christ

The German research team

Germany is one of the destination countries in western Europe for people who have to flee from their homes. In BICC’s fieldwork in Germany that we are responsible for in the project, we use different qualitative methods: semi-structured interviews, biographic interviews, expert interviews and focus group discussions. After we had to postpone fieldwork due to the COVID-19 pandemic, empirical fieldwork in Germany started in August again.

The German research team consists of the BICC staff members Simone Christ (responsible for the TRAFIG field research in Germany), Benjamin Etzold (TRAFIG scientific coordinator), Maarit Thiem (TRAFIG project coordinator), Gizem Güzelant (student assistant in TRAFIG who is currently writing her master’s thesis at the University of Bonn within the TRAFIG project), and four students—Mara Puers (University of Cologne), Juliette Simon (University of Trier), David Steffens (University of Trier), and Philipp Themann (University of Bonn)—who are going to write their master’s thesis related to the TRAFIG project.

Unexpected challenges: Fieldwork and COVID-19

Even though we were able to resume field research face-to-face from summer onwards, this is now very different from our usual fieldwork experience. Whereas previously, when conducting field research with refugees in Germany, we got to know refugees in welcome cafés in the shelters or accompanied them to their appointments at different agencies; in a nutshell, we were able to immerse ourselves into the field. With COVID-19, all this is no longer possible. Our concern now is to ensure that we do not put our respondents and ourselves at risk and to strictly follow the hygiene standards. Access to the field is thus proving to be much more difficult than it was before.

Another challenge to every research situation with refugees is that there is a power difference between us, the privileged researchers, and our interviewees, most of whom are in vulnerable situations. This power imbalance is even more striking in this current health crisis, as, for example, some of our interviewees still live in refugee shelters with shared rooms, bathrooms, and kitchen, where keeping a physical distance is just not possible.

Preliminary findings

Protracted displacement in Germany?

The term protracted displacement is usually used in the context of displacement in the Global South. Can we also speak of this in western Europe? Based on our research, we argue that protracted displacement also exists in Germany. Refugees whose asylum application is rejected but who cannot return usually receive a temporary suspension of deportation; they are tolerated in Germany. Very often, this situation lasts for many years. These people are de facto excluded from any integration measures such as language courses or access to the labour market. The tolerated stay becomes protracted, hopelessness and legal insecurity determine their everyday lives for many years.

Feben is one of them. Feben is a young woman from Eritrea whom I met several weeks ago. Her asylum application was rejected, but she has a tolerated stay. For three years already, she has been living in limbo—she does not have a work permit and cannot do anything else than waiting. Feben tried hard to get a work permit by approaching the foreigners’ registration office, yet she has been unsuccessful. She told me:

"I would like to learn, do an apprenticeship and live independently. I do not want to sit like a poor woman only at home. I am young, I have strength, I want to work. Now I am like an old woman, sitting at home, getting only money from social services. I asked for a work permit a thousand times, but the social security office said I shouldn't come here anymore.“

Container shelter in NRW, Germany. Photo: Simone Christ, BICC

Container shelter in NRW, Germany. Photo: Simone Christ, BICC

Mobility

The mobility of refugees in Germany largely depends on the legal status they have. Under the Geneva Convention, recognised refugees can travel freely, except for their return to their country of origin. Nevertheless, they are facing mobility restrictions—In Germany, they are not allowed to move from one federal state to the other within the first three years. Asylum applicants or people whose deportation is suspended must even ask the foreigners’ registration office for permission to leave their municipality.

This can lead to paradoxical situations, such as in the case of Mehmet: Mehmet found a well-paid job that corresponds to his qualifications within a relatively short time. However, he is assigned to a refugee shelter in a small town in North Rhine-Westphalia, around 150 km away from the city where he found the job. As his asylum application is still pending, he is not allowed to move there, even though the foreigners’ registration office allowed him to take up this job.

Connectivity

The interviews conducted so far show that among refugees there are different degrees of connectedness: Some have large networks; others’ networks are disrupted. Asma, a woman from Syria, has built up local and transnational network contacts. When Asma arrived five years ago, she befriended a German woman. As her daughter goes to kindergarten, she got to know some of the other children’s mothers. Besides her local contacts, Asma also depends on her transnational network for support. Having had a stillbirth, Asma is pregnant again. Her family, in particular her mother and her two sisters in Syria, are her source of transnational emotional support. Whenever Asma has an appointment at her gynecologist’s, they think of her. Asma reports: “They all have my doctoral appointments in their calendars. After the appointment, when I go home, I contact my mother and my sisters.”

At the other end of the spectrum is Nadim, a young man from Syria. Even though he learnt German quickly and tried hard to get to know other people here in Germany, he did not succeed. Nadim feels lonely: “No one has visited me at home for two years.” He has also lost all connections with his former friends in Syria. It is only his core family, his sister in Germany and his parents in Syria, with whom he keeps contact.

The relation between mobility and connectivity: The case of family reunification

The interlinkage between mobility and connectivity becomes apparent in the case of a family reunification. A family reunification enables refugees stuck in countries of first reception or transit countries to be mobile by building on familial connectivity. Only members of the core family are entitled to family reunification. Even though recognised refugees have the right to privileged family reunification, it is often a long-lasting and emotionally very demanding procedure.

Between 2016 and 2018, people with subsidiary protection were no longer allowed to enjoy mobility through family reunification, and to-date, a maximum of 1,000 people per month can apply for reunification. Two years may seem short. But what about children who are separated from their parents for years? What is the emotional cost of having to maintain parent-child relationships only via WhatsApp?

The case of Dahab from Eritrea tells us about the burdens of a protracted and undetermined family reunification process. Her two children who are under-age live as refugees in Ethiopia. Dahab applied for privileged family reunification back in 2016. But the road to family reunification has been and continues to be very rocky— bureaucratic hurdles have so far prevented Dahab’s children from joining their mother in Germany.

In April 2020, the children had an appointment at the German embassy to apply for a visa. But as a consequence of the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the appointment was cancelled, and the children have so far not received an alternative appointment. Just a few days before I started writing this blog post, a violent conflict began in northern Ethiopia, where Dahab’s children live. The region is blocked, and reliant information is missing. Dahab has been trying to get in touch with her children, yet unsuccessfully. After having waited for so many years, the situation has become even worse: Besides the difficult situation around the mobility of her children to Germany, now her connectivity with her children has also been disrupted.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the TRAFIG Consortium or the European Commission (EC). TRAFIG is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.

Asylum reception during the pandemic: How can systems become more resilient?

By Caitlin Katsiaficas and Martin Wagner, ICMPD

The Covid-19 pandemic has resulted in a number of far-reaching impacts on daily life across Europe, and asylum systems are no exception. With the outbreak, the accommodation of applicants and beneficiaries of international protection in reception facilities has posed several concerns related to the health and care of both residents and staff which have spurred a host of changes across European reception systems and facilities – with important implications for residents. Reception is a key first step in providing an effective solution to displacement for asylum seekers in Europe. It is not only part of a state’s obligation to provide protection and access to asylum, it is also the first entry point into receiving societies, providing orientation, accommodation and other key introductory services. Covid-19 has had a significant impact on both the functioning of reception systems and facilities and on the lives of asylum seekers and refugees in reception.

Immobility perpetuates insecurity and a life in ‘limbo’

Social distancing is a huge challenge in centralised accommodation, putting vulnerable individuals particularly at risk. Additionally, the pandemic has shifted attention away from other health issues, including mental health, which may be exacerbated by the pandemic. But beyond (the more obvious) health concerns, the pandemic has also presented a range of other challenges for residents. In many cases, activities such as language classes and internships have been suspended, disrupting not only residents’ routines but also their longer-term integration prospects (a challenge compounded by economic downturn and rising unemployment in receiving societies). Also important to integration and social cohesion are relationships between asylum seekers and refugees and receiving communities – but these have at times soured, worsened by fears related to the pandemic’s spread. Meanwhile, mobility restrictions and public health concerns have also led some systems to pause exits from reception, leading to longer waiting periods in legal insecurity and potential negative mental health effects for residents. However, pushing people out of reception can also lead to challenges, especially when finding a new apartment or a job is made even more difficult by the pandemic. Covid-19 has therefore had shorter- and longer-term implications for residents, of which a prolonged sense of insecurity is a central feature.

“Every emergency, when you are not prepared, exposes the weakness of the system.” Apostolos Veizis, Médecins Sans Frontières Greece

Reflecting on recent developments, participants in a TRAFIG expert meeting identified the following lessons learnt thus far for strengthening the response of reception systems:

“There will be a new normal after Covid-19, within reception systems as well as the broader asylum system.” -- Michael Kegels, Fedasil, Belgium

Strategic communication, technology and flexibility as potential game changers

While national contexts differ, Covid-19 has had important similarities in its impact on the lives of those in reception across Europe. And although the health situation in Europe has improved, concerns about local outbreaks or a second wave remain and the wait for a vaccine continues. Beyond health concerns, one of the largest impacts of the pandemic has been an intensified and prolonged sense of limbo for residents. Furthermore, there is a danger that imposed changes like limited access to the territory, asylum procedure or reception will not be fully rescinded but instead may be prolonged even under an improved health environment to serve a longer-term political strategy. With Covid-19 the second major shock to reception (and asylum) systems in the past five years, the pandemic provides an important opportunity to reflect and find ways forward to strengthen this key phase in providing durable solutions. Strategic communication efforts and the creative use of technology, combined with increased system flexibility, are some potential game changers that can be leveraged to make reception systems more resilient going forward and to better support residents as they wait to settle in their new communities.

This blog post is inspired by a TRAFIG meeting of reception experts from Belgium, Germany, Greece and Italy held in June 2020. The discussion of the impact of Covid-19 on reception systems and residents touched upon several of TRAFIG’s central themes, namely 1) the complexity of navigating within aid and asylum governance regimes; 2) living in limbo, including the legal and psychological insecurity and immobility that it entails; and 3) the importance of fostering good relations between displaced persons and hosts.

The pictures show Covid-19 adaptation measures in an asylum reception facility in Belgium. Photos courtesy of Fedasil, Belgium.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the TRAFIG Consortium or the European Commission (EC). TRAFIG is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.

Asylum reception during a pandemic

The impact of Covid-19 restrictions on the lives of applicants and beneficiaries of international protection in reception in select European countries

Private stakeholder meeting 9 June 2020

The Covid-19 pandemic has resulted in a number of far-reaching impacts on daily life across Europe, and asylum systems are no exception. In this context, the accommodation of applicants and beneficiaries of international protection in reception settings poses many concerns related to the health and care of residents and staff. Since the outbreak, a variety of measures have been put in place in different reception systems and centres, including restrictions on movement, quarantines, the pausing of education- and work-related activities, and bans on or separate accommodation for new arrivals. The consequences of such measures to halt the pandemic’s spread also pose a concern for the wellbeing and integration of this population.

With reception a key first step in providing an effective solution to displacement – and one that has come under increased stress since the 2015-2016 spike in arrivals and now the Covid-19 pandemic – participants in this expert meeting exchanged experiences, challenges and good practices and examined the impacts of recent developments on both reception systems and those in reception facilities.

Read more about it here