"Some things should be kept unclear"

Researching Congolese in The Netherlands

By Catherina Wilson, Oussama El Khairi and Sapin Makengele, 11.04.2022

A small team from Leiden University undertook exploratory research amongst the Congolese community in The Netherlands to better understand both their local embeddedness and their transnational networks. Yet, the researchers often encountered skepticism, silence and rejection. What can we learn from their experience, about the ‘ongoing limbo’ of many Africans living in The Netherlands, about research methods and ethics in such a large project, and about ourselves as researchers?

The Research

The initial purpose of our research amongst the Congolese community in The Netherlands was to trace flows and transnational networks that connect the Dutch Congolese diaspora to other Congolese diasporas in Europe and Africa. In particular, those living in countries where TRAFIG research has been conducted (Germany, Italy, Greece, Tanzania). The choice for The Netherlands was, on the one hand, pragmatic (this is where we live, work and study). On the other hand, it was an opportunity to move beyond colonial, language (and also research) legacies: the more visible Congolese communities in Brussels and Paris (the epitomes of the Congolese Diaspora) have received more scholarly attention.

The team was constituted of three collaborating researchers: Sapin Makengele, a Congolese artist/painter living in The Netherlands and an active member of the Congolese community who shared some of the same experiences as the participants; Oussama El Khairi, a Moroccan MA student at the Leiden University (African Studies); and Catherina Wilson, a Belgo-Colombian post-doctoral researcher at the Leiden University working on mobility issues. Since our first meeting, this project was shared, co-creative and rhizomatic in its hierarchy. Each of us apported knowledge to the whole and we developed the research together from the outset (For an inspiring example in a different context, that of the Indian community in England, see Puwar 2011 'Noise of the Past').

Sapin’s input did not only relate to his creative skills, but also to his previous experience as a research assistant to several historians and anthropologists in Congo. In this research, however, Sapin was not merely an assistant, being part of the community, Sapin was an important gatekeeper who actively looked for people, set up meetings, held interviews and observations, but also translated and took part in the analysis of data. Oussama contributed with his visual readings and cinematic knowledge. Together, Sapin and Oussama, became a team, an ethnographic couple, an older and younger brother who, amongst others, produced a short video explaining their research approach (“Congo in The Netherlands”). Catherina’s role was to connect Oussama to Sapin, to participate and walk along when asked to do so, but especially to keep herself at a distance, as a background observer and facilitator. With regards to our positionality, the three of us are migrants, yet to different degrees, of different origins and with different trajectories. Sapin doubtless standing with one and sometimes two feet in the Dutch Congolese community.

Out of the 22 potential participants we approached and talked to, only 7 ended up participating. Hence, we broadened the scope from Congo to Sub-Saharan Africa. In the small sample of seven people, four participants are originally Congolese (Kinshasa), one is Angolan, one is from Congo-Brazzaville and another one is Zimbabwean. Three out of the seven hold the Dutch citizenship, and one is a Belgian citizen. There are four women and three men; their ages vary between 20 and 70 years. Most hold a higher education degree and work in different sectors covering arts, logistics and social work, among others. Forced (or perhaps blessed?) to choose depth over width, we visited all the participants more than once and had different follow-up phone calls and instant messaging conversations. During our visits, we took a biographical approach, held open-ended interviews (without fixed guidelines) intertwined with participant observation and informal conversation. All interviews were recorded (with consent of the participants), either on audio or on film.

Sapin interviewing research participant at her home (Photograph by Oussama El Khairi, April 2021)

Sapin interviewing research participant at her home (Photograph by Oussama El Khairi, April 2021)

Oussama filming Congolese musician at his house (Photograph taken by Sapin Makengele, March 2021)

Oussama filming Congolese musician at his house (Photograph taken by Sapin Makengele, March 2021)

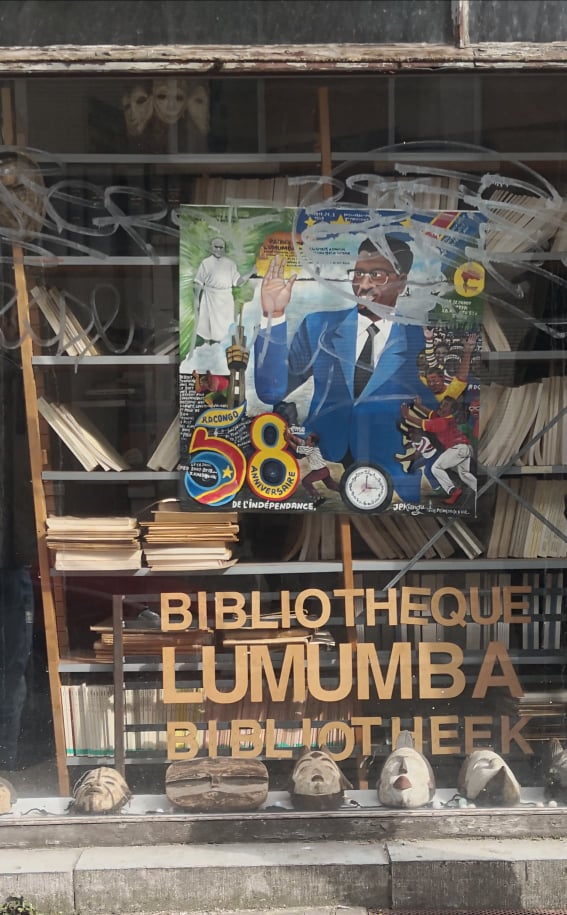

The role of observations

Our participant observations played a crucial role in shaping data and analysis. We attended, for instance, a church service (in Utrecht) five times: twice physically and three times virtually through Skype. The members of the church were mostly first and second generation migrants with roots in various Sub-Saharan African countries. After Covid-19’s enforced lockdown, this resilient group soon found their way to virtual communication. The church sessions and cults were delivered mainly in Dutch or instantly translated into Dutch in the case of international guest speakers. The members of the church showed a high sense of belonging and attachment to their church and religion, which manifested itself as solidarity within the community. Observations also took place in an Afroshop (that is a shop where one can find African food and other goods and that, often case, serves as an informal beer bar) and during a daytrip to Brussels (that serves as the cultural and economic capital of the Congolese community living in the BENELUX, see, for instance, the bibliothèque Lumumba hereunder).

With regards to language connectivity, we detected similarities between the shop and the church. In both spaces, individual prefer to interact with others who belong to the same linguistic group (for instance Francophone or Anglophone). To interact beyond one’s own linguistic group, however, individuals switched to Dutch. In contrast to the church’s communal feeling, individualism seemed to be more dominant in the Afroshop. Also, the question of gender cannot go unseen: during out visit the Afroshop’s clients were mostly men, while at the church there was gender diversity.

Bibliothèque Lumumba in Matonge, Brussels’ ‘Congolese neighbourhood’. In comparison to The Netherlands the Congolese community in Belgium is more visible (Photograph taken by Oussama El Khairi, April 2021)

Silences

In her research on 19th century slave flight in the American urban South, Viola Müller guides our attention to the silences and gaps in historical archives and encourages us to find innovative ways to read existing sources, such as asking negative questions, bringing together fragmentary voices and drawing reverse conclusions (Müller 2020, 17–18). Similarly, in our research, we can learn from what has not been said or was scarcely mentioned. At hindsight, silences and omissions, as frustrating as they were, guided us to core issues individuals in the Congolese diaspora in The Netherlands have to deal with: identity, fitting in, integration, (structural) inequality and racism, the hope for a better future and nostalgia.

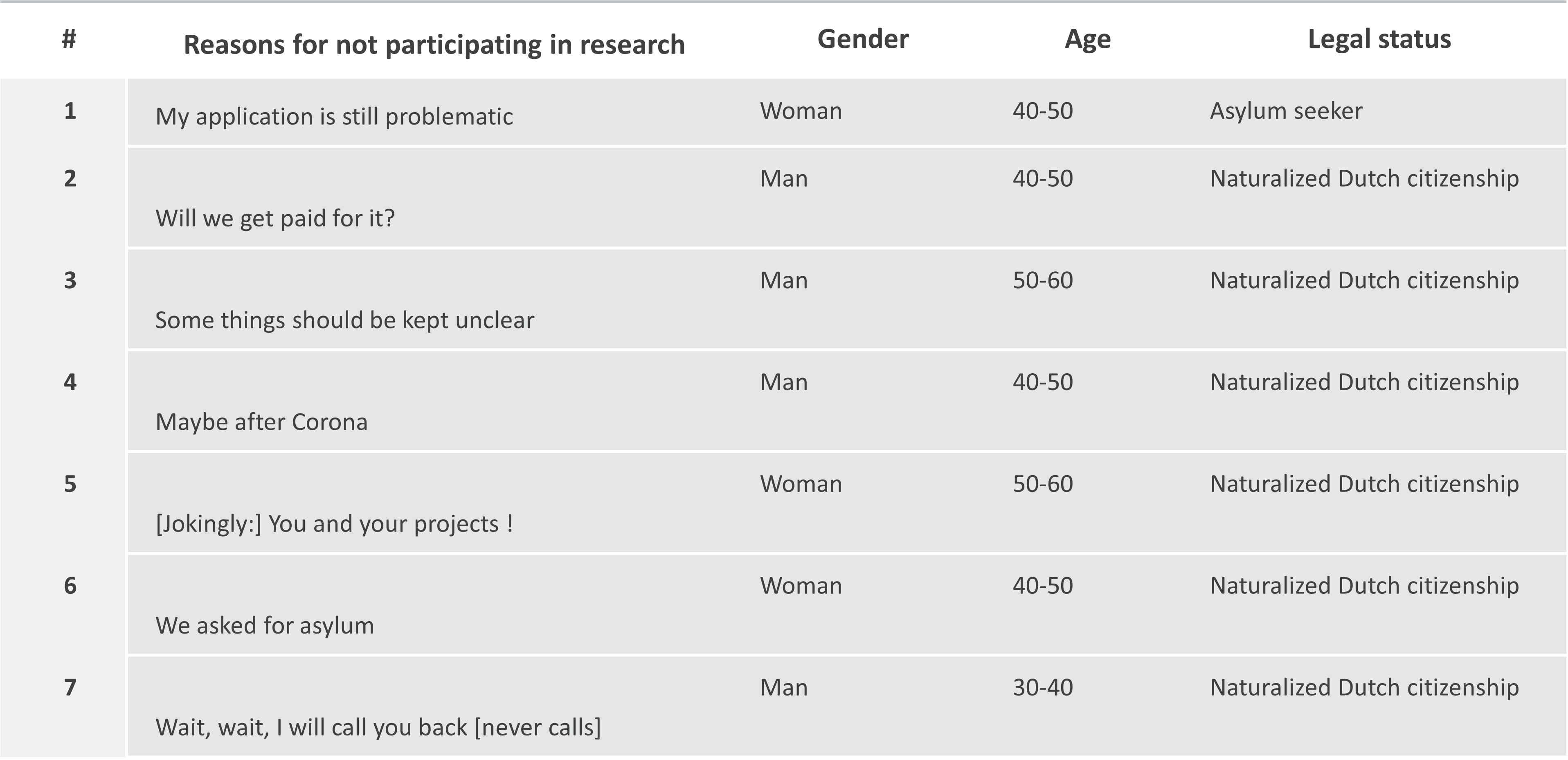

We were triggered by understanding the motives behind potential participants’ abstinence from our research, often revealed off-record during more informal conversations, that is participants who had agreed to be interviewed in a first instance and then withdrew. On the one hand there was a willingness and perhaps a need to tell one’s story, on the other hand there was fear to reveal one’s identity and process in obtaining a legal status. But, what was their silence telling us? While we cannot share confidential information, we can ‘draw reverse conclusions’ by looking closer at the reasons for not participating, listed in the table hereunder.

There are three points worth commenting on. First, it seems that the adult working generation is, generally, more careful and less open about sharing their story than the younger (students and in some cases also second) generation. Second, and perhaps the most striking observation, for the working generation, the legal status did not play a role with regards to disclosing one’s personal story. In other words, potential participants with a permanent status (the Dutch nationality) still felt the need to be careful. This will be further discussed in the section hereunder. Third, curiously, we never got a clear denial, a concrete NO to our request of participation. Examples 4, 5, and 7 in the table above serve as polite rejections, probably because an open decline would be too impolite and impact the personal relationship.

An ongoing limbo?

Even if working with Sapin was very helpful to get in touch with different Congolese individuals in The Netherlands, the initial enthusiasm expressed by different people to participate in our research soon faded away. Slowly but surely enthusiasm turned into apprehension, especially when the request, and our answers to questions, became concrete and official: “Yes, we are a team of three and there is a MA student writing a thesis about it”, or “Yes, we will record and if you allow us, film, for this purpose we need your explicit consent, but don’t worry we will anonymize the data”, and “Yes, it is part of a bigger EU-funded project…”. It was as if every time we tried to take a step closer, we were in fact taking two steps backwards. It puzzled us.

The COVID pandemic and the consequent lockdown periods were of influence, as we could not meet people spontaneously, but had to set up concrete meetings, wear masks and at times even hold interviews online. COVID created more distance, but that was not it. As mentioned above, we noticed a difference in generation, younger and second generation migrants seemed fairly open to talk about their experiences. In fact, they were particularly keen in denouncing structural racism and the glass ceiling preventing them from rising beyond a certain professional level in society. The integration process, for them, including its regulations and conditions, was perceived as paradoxical and hard to meet. Those who successfully walked the “naturalization” path, were thought to be successfully molded; even if they held onto their origins.

People in precarious legal situations were cautious about sharing their personal stories, and understandably so, the risks of being sent back as the asylum procedure was still ongoing hovering over their heads. Nevertheless, one of the participants who did agree to take part, a young man in his early twenties, found himself in this situation. We were puzzled when we noticed that the feeling of ‘having to hide oneself’, was not less present among the people whose asylum was granted more than a decade ago and who obtained the Dutch nationality years ago. It was as if their nationality could be rebuked.

This finding raises interesting questions: Does protractedness extend after settling the legal status? And if so, can we then talk about an enduring state of psychological/emotional limbo where there is an unwritten law that forces people to put on the the correct “modern” or “civilized” make-up to be considered as full (first class) citizen? Is the so-sought after integration, then, ever achieved? How can we tinker with Western ideals of integration so that they are more realistic and welcoming for migrants and their descendants, also with regards to future generations? Or will be certain migrants condemned to remain in limbo?

Ethical considerations and the Leiden Statement

Putting ourselves in the shoes of Congolese migrants in The Netherlands, we should ask ourselves the question why would a participant tell his/her story to an EU-funded project if, in first instance, it is the EU that does not want him/her in its territory? A very legitimate question indeed. Conversely, this question helps to formulate the dilemma in which researchers working with (undocumented) migrants find themselves. In other words, ethnographic researchers are confronted with an ethical conundrum in data management: How can we (the researchers) guarantee full anonymity, and safety, to research participants without losing important in-depth details of their stories? Is changing names and switching to pseudonyms enough? This is particularly poignant in projects such as TRAFIG that demand written and signed consent forms and raw data-sharing with a wider group (see TRAFIG’s Ethic Guidelines and Carolien Jacobs’ reflections on the process of formally getting informed consent).

The Leiden Statement might hint at potential solutions. The starting point? Practices from the quantitative sciences cannot be blindly adopted in a qualitative work based on a social exchange that is constantly negotiated and based on relationships of trust as Peter Pels and colleagues argue. The EASA’s Statement on Data Governance in Ethnography, based on the Leiden Statement, succinctly summarizes qualitative data governance in six points:

EASA’s Statement on Data Governance in Ethnography

.png)

Can we then write about ‘things that should be kept unclear’? We believe we can, and we should. Herein the details are not just additional accessories that beautify stories, but important elements towards a fuller understand of how uncertainty, hampered mobility and structural racism are lived, experienced and embodied. So, the question is not if, but how to write about ‘things that should be kept unclear’? A previous blog called for opacity and incompleteness and tried to focus on objects instead of people (Wilson 2021 ‘All for a Bag’). This is one option out of a myriad of ways to deal with this conundrum.

What we really need to do is to think out of the box, embrace art, experiment with creative methods, write real-facts-based-fiction, tell stories and use visuals. We should do this not because it is less academic, on the contrary, we should do this because it would help us to write about, to express and to deal with the unwritable.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the TRAFIG Consortium or the European Commission (EC). TRAFIG is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.