Migrant integration in times of the lockdown. Some reflections from Italy

by Ferruccio Pastore, FIERI, 23.03.2020

If there is a silver lining, however thin, in the crisis we are going through, it has to do with the greater reflexivity it forces upon us. Isolation and routine disruption make us reflect more upon things we too often took for granted. Among these, the nature of our personal and social ties, and the extent to which they are context-dependent. More particularly, for us as scholars working on migration, the lockdown situation brings a new perspective on issues such as ethnic boundary-making and migrant integration.

How will the pandemic impact such processes? Will it widen existing cleavages and exacerbate prejudice, as it happened so often during past epidemics? Or will it, on the contrary, help bridging ethnic and cultural boundaries by raising awareness of interdependencies and of the necessity to cooperate for collective risk reduction?

The risk of vicious circles

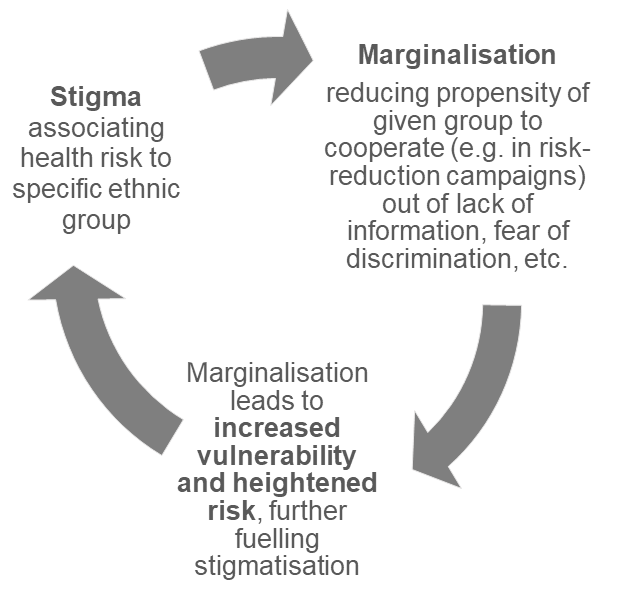

With these questions in mind, the first days of the emergency in Italy, punctuated as they were by sinophobic aggressions and delirious blame games, were of ill omen. As time goes by (and contagion gains ground and speed), a less disruptive climate seems to prevail. Even the most unscrupulous political forces show more self-restraint. Targeted solidarity campaigns launched by minority groups seem to reach some of their intended symbolical impact . Defusing and, if necessary, de-escalating processes of ethnic stigmatisation is vital. Not only out of a moral imperative, but also to forestall dangerous vicious circles of the kind that health sociology has described (e.g. in the field of mental health. In the figure below I try to sketch some of these potential dynamics.

But, even if the Italian society will confirm it has sufficient cultural and moral immunogens to resist the temptation of ethnic scapegoating, migrant integration still appears at high risk.

Systemic crises and migration-related inequalities

Past systemic crises, such as the one unleashed in 2007 by the (financial) virus coming from west, taught us that migrants tend to be disproportionately hit. This was particularly evident in southern Europe, where migrant-intensive economic sectors were among the most severely affected

In Italy, in particular, the never-ending economic crisis that started in 2008 reinforced an already existing trend of ‘ethicisation of poverty’ . The ‘Citizens Income’ (Reddito di Cittadinanza, RdC) introduced by the Five Stars-Lega government in 2019, with its strict (and de facto discriminatory) length-of-residence requirements, didn’t correct unbalances. One year since its launch, non EU nationals are only 6% among RdC recipients, while they are estimated to represent up to one third of persons in absolute poverty.

In this context, COVID-19 risks to make things even worse, operating as a multiplier of migration-related inequality. The regions where the impact of the virus has so far been heavier (Lombardia, followed by Emilia-Romagna, Veneto and Piemonte) are also those hosting the largest immigrant communities. Disproportionally concentrated in informal and seasonal activities, with more precarious contractual positions, migrant workers often lack social protection and are therefore more exposed to the short-term occupational impact of the epidemic. A bitter paradox needs to be highlighted. While, on one hand, immigrants’ position in the labour market is weaker than average, on the other hand they are over-represented in those vital activities (logistics, agriculture, elderly care) that cannot be stopped even in times of lockdown and social distancing. While Italians are strictly required to ‘stay at home’, we keep asking immigrants to grow and deliver our food, and to keep providing us with care services under conditions of growing stress and risk.

One final word about collective settlements. Even with new arrivals by sea at relatively low levels (2,738 as of 19 March 2020), over 85,000 migrants, beneficiaries of protection and asylum-seekers are still hosted in the different branches of the Italian reception system. Their life conditions, already compromised by recent restrictive reforms, are now further jeopardised. Without enhanced and targeted protection measures, all mass accomodations are at higher contagion risk , and when they host recognisable minorities the additional risk of stigmatisation is always looming.

This contribution is a translated and slightly adapted version of the blog post “L’integrazione ai tempi del contagion” published on 17.03.2020 on https://www.neodemos.info/articoli/lintegrazione-ai-tempi-del-contagio/

The views and opinions expressed in this blog do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the TRAFIG Consortium or the European Commission (EC). TRAFIG is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.